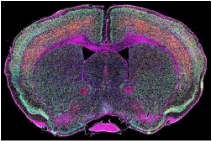

Kenison Garratt Editor-in-Chief and A&E Editor Scientists at Ohio State University have succeeded in growing a near perfect embryonic human brain. Researchers have been making brain organoids for less than a decade, and already they have succeeded in the creation of an organoid containing ninety eight percent of cells existing in the brain of a human fetus at five weeks. In 2011 an embryonic brain was grown by Madeline Lancaster, a scientist at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, but Ohio State’s organoids are different because they have most of the brain parts. These “mini brains,” grown in petri dishes from skin cells, are just scraps of tissue between two and three millimeters long, and yet they will be incredibly helpful in drug testing and treatments against disorders and diseases. These brain organoids will be used to mimic the brains of those suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease and then studied to see how they react to treatment. “Mini brains” could also help scientists to further understand schizophrenia, epilepsy, traumatic brain injuries, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Testing on these organoids could allow doctors to discover better individual treatments. While the project is still in its early stages, scientists predict brain organoids could lead to discovering new treatments to some sub-types of autism within ten years.

The future for organoids is promising, and the results of their research could lead to larger organs being grown for transplants. This is the goal of a group of scientists from Australia and the Netherlands who have succeeded in growing mini kidneys equal to human kidneys during the first trimester of development. “If they could be induced to express more of the organ genes and can be grown into complete organs (or at least larger tissues of organs),” says Jeffrey Derda, Apex High astronomy and biology teacher. “I could see a very real benefit in the world of geriatric medicine and/or transplant surgery.” These organoids will be excellent in testing the toxicity of new drugs, possibly even replacing animals in laboratories, because they include the cell types most vulnerable to damage by drugs. Grown from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, these kidneys include twelve of the twenty cell types which make up human kidneys. In the past, stem cells were commonly used for this type of research. Yet, in the last few years, stem cells have been replaced with iPS cells, which are cells taken from human tissue and made to behave like stem cells. Derda believes stem cell use would be the main cause for concern among the public on the subject of organoids, “As for society as a whole, any time stem cells are involved there will be those who question the source of the stem cells and label research with stem cells controversial or morally questionable. While I don't feel that stem cell research is wrong if conducted with scientific validity, many others don't share my view that the benefits will outweigh the negatives.” These small kidneys will definitely be helpful. However, since they are not fully grown organs, they are unable to be used in transplants to help patients dependent on dialysis, but scientists are determined to one day create the kinds that can. “The other thing about research is, the biggest breakthroughs may come from an avenue of research we cannot even anticipate or envision at this time,” explains Derda. “You never know what tomorrow may bring. This obscure, potentially controversial topic today could be the backbone of a commonplace cure or therapy in the future.” Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|